Remembering Joshua Clover

We are deeply saddened by the death of Professor Joshua Clover

Professor of English and Comparative Literature Joshua Clover died on April 26, 2025. Here Joshua’s students remember him.

It is with great sadness that we announce the passing of Joshua Clover (1962-2025). Joshua was a professor, theorist, scholar, editor, and poet, but first and foremost, he was a communist. Indeed, his political commitments were at the core of everything he did: from the streets to the courthouses, the reading groups to the letter-writing nights, he was a partisan of the real movement wherever it could be found.

Joshua joined the UC Davis English Department in 2003 as a professor of poetry and poetics. He earned an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1991 and published three volumes of poetry: Madonna anno domini (1997), which won the Walt Whitman Award from the Academy of American Poets, The Totality for Kids (2006), and Red Epic (2015). His poems have been praised for their formal precision, glowing visual language, and unflinching political clarity. As a scholar, he authored numerous works on subjects ranging from poetics to political economy. At the end of his life, he was working on a new book manuscript, tentatively titled Infrastructure and Revolution.

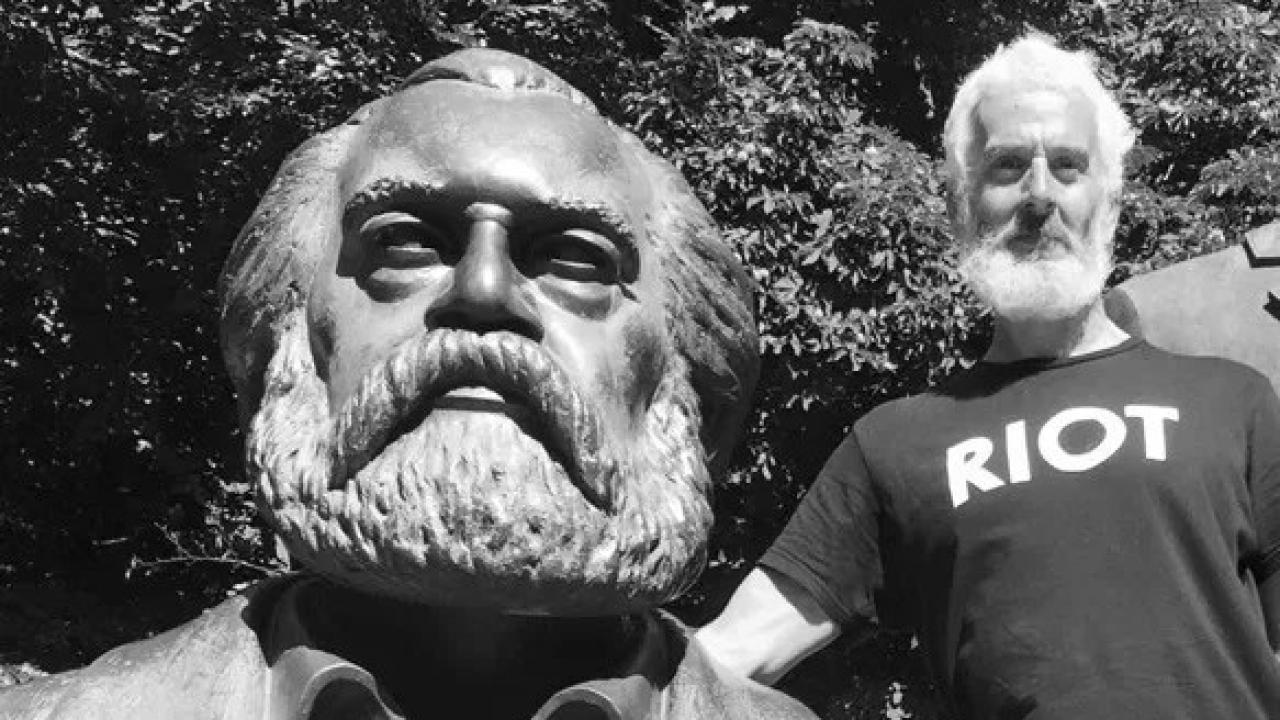

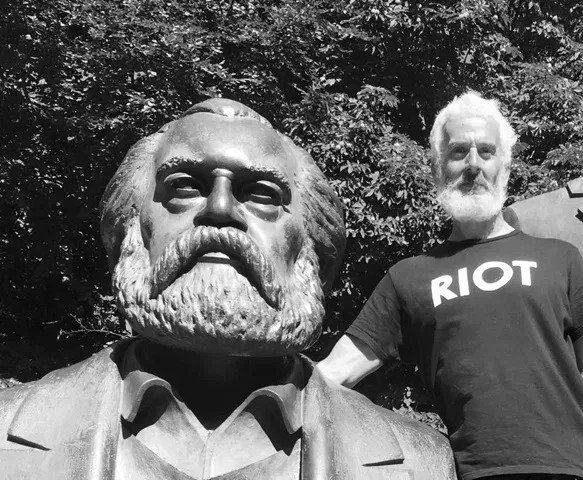

Five years on from the George Floyd Uprising, his contributions to political analysis deserve our continued attention. His book Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprisings (2016) is considered a tour de force of contemporary social theory. Offered as a lucid distillation of the often turgid and opaque debates of the communist left and a resolution to its theoretical dissonance, Riot. Strike. Riot. is, at its best, what all communist inquiry strives to be – mere words put to paper, grasping at the real movement of history in an attempt to intervene. Always economical with his prose, Joshua captured the complexity of capitalism’s historical development and the particular forms of struggle that attend it with pithy locution and often devastating precision. Riot - strike - riot’. A nimble formula and a détournement of Marx’s M-C-M’ (i.e., money - commodities - more money), it is also a history of the disaster we call capitalism. Joshua’s work revealed circulation struggles as the horizon, or limit, of social conflict today, identifying the riot, the barricade, the infrastructural blockade, the protest camp, and the commune as the forms adequate to our historical moment. He showed us that it is only by overcoming the separation of production and circulation, town and country, and the division of labor that these struggles can generalize. We call that moment of realization the end of capitalism. Or, if you prefer (as he would), the beginning of communism.

Though he looms large in the world of political and social theory, he was equally a scholar of contemporary culture. His publications include a book on The Matrix (2004) and two on music: 1989: Bob Dylan Didn’t Have This to Sing About (2009), which explores the musical landscape surrounding the fall of the Berlin wall, and Roadrunner (2021), a circuitous meditation on the titular song that captures the dizzying spiral motions of a world in crisis. He also wrote prolifically for public-facing publications, including regular contributions to The Village Voice, The New York Times, the Verso blog, and elsewhere.

In his role as professor, Joshua taught seminars and directed dissertations across many departments and programs, including English, Comparative Literature, Cultural Studies, and Critical Theory. He was one of the founding members of the Marxist Institute for Research, a research cluster promoting Marxist methods and supporting graduate student scholarship across the ten UC campuses. His seminar on Capital was frequently filled beyond capacity, and he introduced generations of students to Marx and the world of critical theory. As a teacher, he was fiery, funny, and unparalleled in his devotion to the success and well-being of his students. His intensity could sometimes be intimidating upon first meeting, but his generosity and firm conviction in the importance of the work quickly made his students feel that they were equal partners in the project of collective inquiry. He liked to joke that he was preparing us to win bar fights, and that may be true, but he was also preparing us for far more consequential struggles.

Joshua was a fixture in the political life of the campus. From the tuition protests of 2009 to Occupy Davis, from abolitionist organizing to Palestine solidarity, from COLA (the wildcat strike) to COLA (the UAW compromise), if something was going down, you could count on Joshua to show up. Even more important than his presence at major events was his commitment to the tedious, often thankless, everyday work of organizing. Many of us will remember him for his seemingly endless energy for that work, for doing what was needed with no recognition and often at great personal risk. He was also a tireless advocate for graduate students, supporting every strike, answering every call for solidarity, and constantly looking for ways to funnel money and resources to those most in need of support. Often, this took the form of little acts of kindness; one of his students recalls how he often worked in his favorite coffee shop and would keep a gift card loaded up and ready to hand off to any hungry graduate student who walked through the doors.

There is so much to remember about Joshua: his unabashed love of pop and country music, his sweet tooth, his endless repertoire of bad jokes. But maybe above all, Joshua will be remembered as a teacher, one whose pedagogy extended beyond the classroom to every space he found himself in, from meetings to picket lines to the streets and back to the buildings of the University of California, especially when seized and occupied by students and staff. In every context, his fierce intelligence and exacting intellectual standards pushed us all to ask better questions, to be more rigorous in our analysis, and always to put our theory into practice. He will be sorely missed.